Story & Art by Ryoko Ikeda

Translated by Mari Morimoto

Lettering and Touch Up by Jeannie Lee

Edited by Erica Friedman

Cover Design by Andy Tsang

The Rose of Versailles is one of the most influential stories in Japanese pop culture. The series is a loose chronicle of Marie Antoinette’s reign as the last queen of France before being ousted and executed in the French Revolution. The story’s primarily told through the eyes of Oscar, a female knight who serves as Marie’s most trusted guardian and confidant. The Rose of Versailles arguably codified several signature stylistic and thematic motifs found in shojo and yuri stories to this day. Oscar, in particular, was such a profoundly resonant character that she popularized the butch, princely woman archetype that has been echoed and reiterated in numerous series since, like Haruka in Sailor Moon and the titular Revolutionary Girl Utena.

Yet, despite its pedigree and historical significance, it’s taken until now for it to receive a full official English translation courtesy of Udon Entertainment. It’s been long overdue, and it’s easy to extol the many reasons to read this series based on its historical merits and legacy. That said, even classics can show their age, especially considering this is already a period piece. Udon’s books look modern and gorgeous, but does the story contained within stood the test of time?

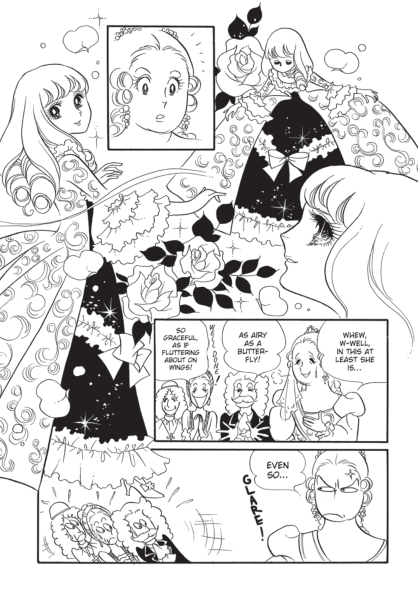

The biggest argument for Versailles’ timelessness is Ryoko Ikeda’s masterfully vivacious artwork. Her gestures and draftsmanship are so effortlessly energized with character. Her lines are simple and clean, sparse, and precise. I notice this especially with her characters’ hair, which are styled with simple outlines and minimally detailed with some curls or just a few line hash-lines arranged in a zig-zag pattern, the effect still looking airy and evocative. Her artistic flourishes extend beyond her character art. She reflects the neoclassical traditions of late 18th-century french through her beautiful dresses, furnishings, and architecture, accomplishing this with very simple shapes and linework. Every character wears clothes that are either pure white with black lines to depict folds or patterns, or pure black with white spaces to convey the same. Oscar has probably the most detailed outfit in the book, and even she just starts out with an all-white uniform only adding a black coat and black boots later into the book.

This book contains a copious amount of Ikeda’s watercolor illustrations, which have more depth in their rendering. These are also quite beautiful, with her characters’ brilliant golden hair and vibrant pink dresses and flowers standing out the most. Still, Ikeda’s pure black and white artwork is so indelibly iconic, and oftentimes more gorgeous than any of her color art. She’s an artist that excels in the minimal, finding beauty in simplicity, and this philosophy seeps through every facet of her artwork.

Perhaps the most stand-out example of Ikeda’s ability to communicate so much with so little is when Oscar reveals the scale of Versailles to Rosalie. Looking at the visual closely, Ikeda draws pretty simple and scribbly buildings and trees and the people are only small little dots, but the effect of the whole is more than the sum of its parts. It doesn’t matter that each individual building isn’t the most meticulously rendered, but that the entire image taken together effectively depicts the scale of the Versailles campus and how huge it is compared to the average person. It looks impressive in scope and illustrates why Rosalie is impressed, which is the intended point and effect. This is one example, but there are a lot of illustrations like this in the book where I can point out Ikeda’s impressive artistic wizardry. It takes great skill to create imagery that looks ornate using very few actual shapes and lines.

Ikeda’s art also eschews shadows and shading for the most part, especially early on. Instead, she gets a lot of mileage out of her art just through the contrast of black ink and against the white page. Screentone isn’t used on characters until around chapter 6, and even afterward it’s sparsely employed, usually used just for dramatic effect. A lot of Ikeda’s effects work appears to be meticulous hand-drawn cross-hatching or pointillism. A great example of the latter effect is employed when she outlines the opera house through a spattering of white-out dots against an inky black background, capturing the vibrancy of its lights and sparkling majesty with nothing but the contrast of white against black. In general, pitch-black panels peppered with white dots and stars are used as a background embellishment to punctuate the character art in the foreground as a sort of dramatic sparkling effect, and it’s employed very liberally and prettily throughout the book. Another trick that stood out to me early on was how Ikeda drew trees and shrubbery as round and cubic shapes and scribbled inside them to communicate leaves. Oftentimes, she’ll shade background elements and characters simply with a bunch of vertical lines. Ikeda’s art embodies the beauty of simplicity.

I think one of Ikeda’s most signature stylistic flourishes as an artist is her distinctive eyes, which also reflect her elegantly simple artistic approach. Nowadays anime and manga characters’ eyes can contain a lot of shapes and colors for an expressionistic effect, but Ikeda’s technique communicates a similar sense of idealized beauty in a really simple way. Her eyes are just black circles scribbled in a way that leaves white space indicating highlights towards the bottom, spotted with a white pupil and punctuated with her signature star-like sparkle. Sometimes instead of the sparkle she instead separates her eyes with a cross-shape that intersects the pupil and evokes the same effect. These are really simple techniques but add another layer of fantastical beauty to her character designs, and it’s easy to see why this stylistic shorthand can still be seen in shojo manga eyes decades later.

One paneling trick that I find unique to Ikeda is this web-like effect that will run across like a page like a crack through a mirror. It’s employed when characters undergo a shocking moment, like when Rosalie and Louis XVI are informed the king is dead or when Rosalie screams in horror upon seeing her dying mother. One of the most brilliant uses of this effect is when Rosalie takes in her mother’s death and dying words. The crack doesn’t just extend across the three bottom panels of the page, like a web ensnaring these dramatic, traumatic visuals and thoughts for Rosalie, but it acts as the word balloon, with a simple “Ah…!!!” at its center. Words alone couldn’t describe the anguish Rosalie’s experiencing in this moment, but having the crack effect wisping out from the word balloon so erratically and uncontrollably displays her emotional devastation with so much more visual impact than her tearful expression could convey alone.

In general, I just love the shapes Ikeda employs for effects across panels to break them up or guide the eye. A really common technique she employs is to run a vertical black bar through a page just to break up the panels, center a character, or guide the reader’s eye through the page top to bottom. It’s an effective compositional trick to divide her panels up, focus the reader’s attention on distinct sections, and emphasize visuals that fall directly in the bar’s path. Ikeda’s paneling and ability to guide the reader’s eye through every important moment in a way that looks clean and reads like a dream is nothing short of masterful. Every page of The Rose of Versailles is a masterfully composed piece of art.

Ikeda’s sound effects also do a great job of weaving across panels in vertical lines that are slightly kerned in a rounded bent. My favorite bunch of these are “Waaaah”’s screamed by Pierre and his mother before after he’s shot by Duke Guememe and the “Baaa…..ng!” of the gunshot itself. I also really love the scratchiness of the “Blaaaze…..” effect when Jeanne lights Boulainvilliers’ house on fire and well as her “Aieeee…….!” scream that follows her after Nicholas pushes her off her mezzanine into the flames. Much kudos should be given to Jeannie Lee for redrawing and lettering these sound effects to recreate the effect of Ikeda’s originals while still complimenting her art.

As beautiful as Ikeda’s illustrations and compositions are, honestly, what I love most about her cartooning is the cartoonishness of it. Sure, she can draw pretty and dramatic faces, but even more endearing are all the goofy and comical expressions liberally employed throughout the book. Ikeda has fun with her characters. They pout with super-deformed faces, fume and scream with sharp-fanged teeth, and give big flat mischievous grid grins when scheming or snarking. She even employs some classical manga shorthands like characters getting stars in their eyes when confused or annoyed, X-shaped crossed-eyes when really exasperated, and even a good old-fashioned whack on the head with a giant mallet when at wit’s end! Oh, and at one point Oscar’s nanny’s head literally pops off, complete with a blood splat and “chop!” sound effect, when Oscar makes a “off with your head” joke to her! Ikeda weaves in and out of her dramatic and comedic moments quite seamlessly thanks to a great handle on tone, so even when really goofy rule-breaking non-diegetic gags like that happen it never really feels out of place. Ikeda clearly had a lot of fun drawing this manga and wasn’t afraid to get silly with her characters even after it shifts into more serious territory. Her sense of humor and willingness to joke around endearingly dynamizes the story’s emotional range, and I really appreciate that she embraces the playful flexibility of the comic medium.

For as much as I gush about Ikeda’s art, it’s undeniable that The Rose of Versailles’s greatest asset is its iconic characters, most especially Oscar. As previously mentioned, Oscar’s popularity spawned an archetype of its own, but her appeal lies deeper than her aesthetic characteristics. Oscar is a gender non-conforming character in a story set in a period of time where the performance of gender was suffocatingly strict. In contrast to her high-society peers, Oscar has been granted greater freedom to express herself. We witness this distinction first-hand in the very first chapter, which explores both her and Marie Antoinette’s childhood. Marie is forced by her mother and handlers to present herself as ladylike and womanly so she can be married off young as part of a political arrangement. Her personhood is treated as less important by her society than her symbolic purpose. She is seen and raised to conform to only one standard, and only what she is expected to be.

Oscar, meanwhile, is utterly and completely respected for who she is by virtually everyone around her and gets to be herself. Sure, her father raises her as his “son,” and trains her as a soldier, but he never denies her womanhood. No one does. Everyone admires Oscar as a skillful soldier and a beautiful woman. She can be both. She is loved and respected by both men and women. One woman literally jokes that she wishes Oscar was a man so she could “force herself on her to be her wife.” I mean, that’s a creepy sexual assault joke, but it speaks to Oscar’s appeal. She’s a power fantasy. A woman beloved by everyone, living mostly free of gendered conformity or sexism holding her back. Oscar, essentially, symbolizes the ideal of a truly liberated woman.

Oh, and Oscar’s obviously a bisexual icon. Riyoko Ikeda’s work was highly influenced the development of yuri and queer manga, Oscar and The Rose of Versailles especially. Both of the other female protagonists in the series, Marie Antoinette and Rosalie, love Oscar way more deeply than any of their milquetoast male love interests. Rosalie especially outright admits she has feelings for Oscar in a subplot that, spoiler alert, sadly resolves in her ending up as a heteronormative housewife later on. Still, the unbridled queerness of the story in how it plays with gender presentation and deep love between same-sex characters remains resonant, and for its time quite revolutionary for a mainstream shojo manga.

Not everyone is totally on board with Oscar’s lifestyle, but their opinions don’t matter. The only character that bemoans Oscar’s lack of interest in dresses and her treatment is her Nanny. There are mixed messages in Nanny’s statements: sometimes her exasperation as Oscar’s unwomanliness is dismissed as a joke, other times they’re presented as sincere concerns. As for sexists, there are only two characters in the book who dismiss and look down on Oscar for being a woman, Nicholas and Duke Guemene. It’s clear these dudes are villains and clowns whose opinions we’re not expected to care about. They also don’t have any power over Oscar. Oscar doesn’t have the legal authority to punish the Duke for murdering a child, but she can still criticize and duel him openly, and Nicholas is her thoroughly incompetent subordinate. They look like idiots for disrespecting Oscar; she doesn’t have to prove herself to them and they know she can kick their ass if she really wanted to. No one we’re meant to respect or care about thinks of Oscar as any less of a warrior or a woman.

At one point Fersen asks Oscar if she’s unsatisfied with the way she lives and not “knowing a woman’s happiness,” and Oscar just chuckles and replies no, “I do not think of this as unnatural, nor have I ever felt lonely.” That’s that. She’s comfortable and proud of who she is and doesn’t feel lacking compared to anyone else. She is who she is, lives her own life, and doesn’t care what anyone else thinks. The fact Oscar is allowed to be badass and beautiful without any caveats, or any messaging implying she has to conform one way or another, is precisely why she was a trailblazing character in the 70s and why she remains enduringly popular.

Oscar isn’t just a great character for her symbolic significance, of course. She’s the moral center of The Rose of Versailles, serving as the bridge between the downtrodden lower-class and the obliviously frivolous elites. As captain of the guard, she’s sworn to protect Marie Antoinette and admires her “regal personage,” but she’s also sensitive to the plight of the French people, who’re suffering under poverty and a lack of resources thanks to the aristocracy hoarding and misspending the country’s wealth. Oscar refuses to accept a pay raise because she knows that money is better spent on the debt crisis, donates money to Rosalie after hearing of her plight, is infuriated by the unjust murder of an innocent child, and journeys to the countryside to assess how the poor masses that make up the majority of the French population are faring. She urges Marie to spend the country’s wealth more wisely and laments the injustice of a system in which the rich can murder the poor in broad daylight and get away with it. She offers her own life in place of Andre’s when his mistake causes Marie’s horse to run wild, monitors and talks Marie and Ferson through their woes of love and loneliness, and mentors Rosalie to guide her down the right path. Oscar embodies nobleness, always wanting to protect the innocent and looking out for her friends’ well-being. She recognizes the good qualities in people of all walks of life and tries her best to be respectful and do right by them. The story’s at its strongest when it’s following her because her valorous perspective is at the heart of its empathetic message. Oscar has a strong sense of justice that allows her to bridge worlds and play peacemaker, but as the story is already hinting, her ideals do not always align with that of her liege, and may put them at odds in the future.

Despite Oscar becoming the face of Rose of Versailles over the years, the manga ostensibly centers Marie Antoinette as its protagonist. Oscar does become more prominent about 200 or so pages into the book, but early on she’s more of a secondary character in Marie’s story. Anyone who knows French history knows how Marie’s story is going to end, and Ikeda frames her story as an inevitably tragic tale of innocence and ignorance. Regardless of how you feel about the real-life person or monarchy in general, Ikeda certainly finds an undeniably sympathetic spin on Marie’s life story. Her Marie Antoinette is a free-spirit, unstudious and undisciplined, who just wants to have fun. She has no desire to rule a country and doesn’t understand the weight of that responsibility. Yet, she’s forced into this role as a child, sold into it being promised that she’ll be admired by all and will be able to do whatever she pleases. Her mother understands that Marie is thoroughly unqualified to be a ruler, but relinquishes her anyway unprepared for anything but partying and looking pretty. There’s something undeniably sad watching Marie have to leave her home, leave behind her old clothes for new ones, and be left behind by her companions; completely stripped of everything Austrian to be handed over to a new land full of strangers to marry some guy she’s never met.

With that in mind, it’s no wonder that Marie spends the entirety of the series chasing happiness, never quite finding it. Sure, Marie’s enamored with the idea of being adored by swaths of people and wearing opulent clothes and attending fancy soirees, but in her heart, she knows she’s unhappy. She pushes her reservations about never being able to fall in love only to be immediately disappointed with her betrothed. She becomes desperately lonely because of her lacking romantic intimacy with Louis XVI. She yearns to fall in love, which leads to her star-crossed affair with Fersen. She also realizes that there are few people in Versailles that see her for herself and not the queen. She clings to her friendships with Oscar and Polignac, despite the latter clearly exploiting her, because at least she can be her honest self around them. She spends extravagantly on Polignac because helping her makes her feel useful and good about herself. Marie was raised to believe that if she was happy, others would be happy for her. So she’s self-centered and makes decisions that benefit her, without realizing how the consequences of her actions affect others.

That said, there are limits to how sympathetic Marie can be. Obviously, Marie is ridiculously privileged and frustratingly selfish considering how ignorant she is of the plight of the people she supposedly governs. We spend a lot of time, through Rosalie primarily, learning how rough the living conditions of the poor are. There’s barely enough bread and rations to go around, there are few jobs because the economy’s tanked, and people are beleaguered by illnesses they’re too poor to treat. Rosalie’s situation gets so bad that she almost turns to prostitution just to have the money to feed herself and her mother, reconsidering only because of Oscar’s generosity. Compared to Rosalie’s struggles to survive, Marie has it ridiculously easy. Her narcissistic spat with Madame du Barry is contrasted with the plight of Rosalie and her family barely struggling to get by, hammering home just how hideously misplaced the nobility’s priorities are. The Rose of Versailles ultimately sides with the French poor and doesn’t shy away from Marie’s culpability in the worsening living conditions and stolen wealth of the French people.

So when Rosalie blames the nobility for her mother’s death and resolves to kill them all, it’s easy to take her side. Because of this, it’s rather frustrating that the series dismisses Rosalie’s grievances with Marie immediately upon meeting her. Rosalie’s instantly smitten with Marie’s beauty and kindness, which seems to immediately release her of any ill-will or misgivings she had, despite her criticism being correct and legitimate. This is the difficult tightrope the series walks with Marie’s character that it never quite balances. While Marie Antoinette may be naive and had the best of intentions, she is not blameless or innocent. Her plight and circumstances are sympathetic, but hers is a story of a prideful downfall that could’ve been avoided if not for her own stubbornness and inability to consider the needs of anyone besides herself.

Though The Rose of Versailles finds a justifiably empathetic perspective on Marie’s life, it’s overall messages of who deserves to hold wealth and power are mixed at best and classist at worst. While the series makes it clear that Marie was ill-prepared to rule France it never interrogates the legitimacy of her royal privilege to begin with. There’s a clear divide between how the series extols “legitimate” nobles like Marie, Oscar, and (as revealed later) Rosalie as unquestionably virtuous while villainizing women like du Barry, Jeanne, and Polignac for buying their way into wealth. Yes, obviously all three of those later characters are unquestionably villains because they try to murder people and are presented as mean-spirited schemers. However, the series frames their rise to power and presence at Versailles as unwelcome and unearned not because of what they did, but because of who they are.

The fact that they come from poverty is, above all else, what makes them targets of suspicion and resentment from the rest of the nobles. Polignac especially is a target of criticism by other characters on the basis of her lack of wealth long before it’s revealed she’s genuinely malicious. Marie’s rivalry with Madame du Barry also has a weird puritanical element to it. Marie’s disgusted that du Barry is the King’s mistress and is allowed at Versailles, and nearly causes a war between France and Austria because she won’t deign to speak with her. Nevermind her disgust is only directed at du Barry, whereas the King is never questioned himself for having a mistress. After Marie is forced to speak to her, she cries that the sanctity of Versailles has been soiled because a “harlot” was talked to like a human being basically. This is praised by Oscar as reflecting Marie’s moral character, because it just reads as weirdly scornful of an adult woman in a consensual relationship. When du Barry is exiled from court, the manga celebrates this as morally just retribution because she spent so much of the King’s wealth on herself. Which is exactly what Marie does as queen, except to a degree so much worse that she causes a war. Yet, Marie’s story is framed as tragic because she was a legitimate noble and is characterized as innocent, while du Barry is scorned because, as someone born of poverty, she supposedly never had a right to wealth in the first place.

Similarly, both Jeanne and Rosalie are daughters of noble families, but the story frames Jeanne as illegitimate because she was born out of an affair, whereas Rosalie is presented as more deserving because she was merely abandoned. It’s strange that women like du Barry, Jeanne, and Polignac, who are ambitious and work to earn their wealth, are treated as villains compared to others who lackadaisically inherit it off no merit of their own. The message appears to be that the only noble nobility are those who earn their wealth through generational wealth, which is a strange moral to send in a story that also explores the institutional corruption of the monarchy and the consequences caused by the wealth gap between the rich and poor.

As messily as the series frames it’s ambitious female characters, they’re still undeniably well-written and fascinating. Jeanne especially is a great antagonist whose confidence artist schemes to break into Versailles, manipulating friend and foe alike, is fun to watch. Polignac is a nuanced villainess, having a complicated relationship with her daughter and Marie that isn’t wholly kind but not entirely malicious either. Even side characters like Nanny and Rosalie’s mom have a surprising emotional depth to them despite their minor roles in the story. This is a fantastic women-led series that centers women of all stripes in interesting roles, developing them with compelling character arcs.

Oh, the male characters are there too, I guess. Even though Fersen is billed as the third-most important character and appears on the first page, he’s pretty simple and doesn’t have much going on. He’s honorable, considerate, loves Marie but knows he can’t be with her because of their respective obligations, and that’s basically it. A good dude, but not much more. Andre is by far the most interesting and dynamic male lead character in the series. Humorously, I don’t think he was even meant to be a major character initially. He’s drawn much goofier in his earlier appearances and mostly serves as someone for Oscar to talk to, either asking her opinion on what’s going on or being clowned on for being oblivious. This changes after Oscar saves his life following the incident with Marie’s horse, after which he dedicates himself to helping Oscar and his emotional intelligence and feelings for her become more pronounced. Andre still hasn’t had a ton to do yet, but his role will undoubtedly be amplified in future volumes. As an anime viewer, it’s just amusing to see that the love of Oscar’s life was originally just some schlubby secondary character that just happened to stick around and get recontextualized as the story progressed. It’s actually quite fun to pick apart the differences between the manga and anime, and I came away preferring the manga’s storytelling overall.

Udon Entertainment’s release is a prestige product worthy of this classic’s golden pedigree. It’s a sturdy hardcover book that can take wear well and is compactly bounded. Andy Tsang’s cover design is immaculate in how it evokes a regal elegance befitting the aesthetics and content of the manga. It employs shiny gold foil trim complemented and underlined with red graphics on top of a white surface, all colors commonly considered royal and prestige. The golden vines decorating the cover are adorned with several budding flowers, and at the top coil into sword-like fixtures. These choices at once employ visual motifs that readily spring to mind when thinking of the series, while reflecting the aristocratic setting of the story. The logo is also prettily designed with a somewhat cursive flair with curled tips to each letter meant to evoke a high-class sensibilities, complete with a diamond-like sparkle punctuating the middle of the “O” in “Rose.” Much like Ikeda’s art, the aesthetics of the cover are in practice simple, but executed so elegantly that it captures the eye with its impressive beauty.

The interior of the book is also resplendent, of course. It boasts glossy premium pages and includes as many of Ikeda’s gorgeous watercolor artwork as possible. The lettering is easy on the eye and fonts are appropriately used in different contexts, with really solid SFX replacements that do a good job of fitting in with and accentuating Ikeda’s art. I particularly appreciate small touches like the Table of Contents including annotations designating which issue of Weekly Margaret a chapter originally ran in, and the inclusion of the original title pages from the series’ run, complete with translations of their cover texts. This is a lovely book to read, and stands out brilliantly on the bookshelf.

The Rose of Versailles was localized by a wonderful team of people passionate about the material and that shows through in the translation. I definitely appreciated the research involved to capture a sense of historical accuracy not only in the dates presented but the manner in which the characters speak. The way characters speak feels appropriate to their backgrounds, and there are subtle differences and ticks characters have that suit their backgrounds. This is most notably with Rosalie, who has a habit of saying “moi, I” instead of just “I.” While redundant, I respect this choice as a dialect reflecting her impoverished upbringing, and this distinction is plot relevant. When Rosalie does venture into Versailles, Oscar criticizes her for the redundancy of saying “moi,” and she’s outed as a commoner at the ball when she refers to her mother as “maman,” which is slang the elites don’t use. Details like these are important to understanding the story and character and the translation executes these nuances flawlessly. I also appreciate the other French phrases spattered throughout the dialogue, like characters exclaiming “mon dieu!” or “merde!” They aren’t necessary, but they add enough flair to remind readers these are French characters in a French setting without being distracting. While the translation is faithful, I certainly found my reading experience enhanced by these fun little flourishes.

I consider myself a fast reader, but The Rose of Versailles took me a while to finish. Not because it was particularly text-dense, but because there was so much to appreciate and unpack in it. Which, summarily, resulted in this queen-sized review. There’s a reason The Rose of Versailles is a classic, you know? I have legitimate criticisms of some of its poor subtext, but the art alone earns it full marks in my book. There’s a lot to say about it, and this is just the first book of five! I admit, I’m interested in how the pacing of the next couple of books is gonna go. This first book encompases like half the plot of the anime, so either the story’s going to slow down a bit in the next book or there’s even more to this story than the anime covered. Whatever the case, I’m here for it, and I hope you’ll be too. Everything’s come up roses, and I’m not seeing through rose-tinted glasses either. The series holds up and there’s a lot more to love. For now I’ll bid you adieu, though there’s a lot more to say. After all, “there’s so many people at Versailles today…”

comments (0)

You must be logged in to post a comment.