Story & Art by Ritsu Miyako

Translated by Molly Rabbit

Edited by Eric Margolis

How do you know when someone’s lying to you? Do they have a visible, physical tick or gesture that gives them away? Perhaps it could be a verbal clue, like the way they speak or their tone of voice, that gives them away. Something that allows you to see right through them. Question is, would you even want to know whether someone’s lying to you? I’m sure that for many people who have trouble understanding the feelings of others, having a way to tell apart lies from truth would be relieving, being more certain whether people mean what they say to you. But think about how often people lie, and why they lie. A lie can be something as straightforward as saying you didn’t take something when you did, or as complicated as saying you’re good when people ask you how you’re doing even though things aren’t going well at all. Not all lies are created equal. Some lies manipulate, others protect. Even if you could parse lies from truth, if you can’t figure out what another person is thinking, the motive behind their lies, then you’re no closer to understanding them. Even so, to better understand other people and to help and be helped by them, you need to be truthful, both to yourself and to the people closest to you.

Usotoki Rhetoric navigates the yin and yang of lies and truth as they relate to connections and communication between people. Protagonist Kanoko is a teen girl who has the power to hear lies – they literally sound different to her, as if a person’s voice suddenly becomes harder, blurry, and metallic, like “a cold ball of steel turned into words.” In other words, she aurally perceives lies as unnatural; she senses the stiff guardedness in a person’s voice, their tenuously supported blending of fact and fiction, and the feeling that someone has forged words and changed their form from their natural state into a weapon turned towards her. As a child, she initially took this in stride. She was downright fascinated she could tell lies apart; it was a new way of understanding people. Unfortunately, because other people in her hometown didn’t share her perceptiveness, they became uncomfortable around her and ostracized her. Afraid of being seen through, it was easier to paint her out to the one who couldn’t be understood, an aberration threatening to unravel a community built on layers of lies. Sadly Kanoko interpreted their insecurity as her fault, internalizing that being able to see through lies only causes trouble for others and exposing the truth as a source of discontent. Where she once excitedly approached others cheerfully exclaiming how they could tell apart their lies, she now perceived them as walls between herself and other people, a tormenting affliction that keeps her from being able to trust in and form connections with others.

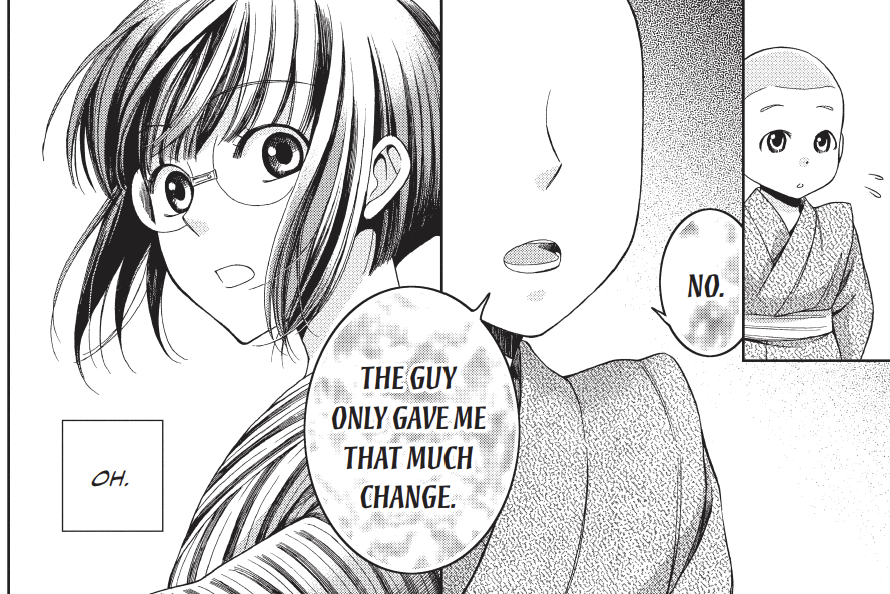

Which isn’t the truth, of course. Kanako has the ability to identify someone’s statements as true or false, but what she hasn’t developed is the emotional awareness to interpret their intentions. She is thus complemented and contrasted by Iwai, a detective whose business it is to understand how people think and the why’s and hows of a mystery. When a young boy lies about keeping change from his parents, Kanako recognizes the lie and chastises the boy, moralizing that lying to people is wrong. Kanako feels lies are always a betrayal of trust, but also puts herself down for exposing them; whether in telling or exposing them, lies only bring unhappiness. Meanwhile, Iwai’s instinct was to notice that the inn’s napkins are of the same material as the scarf of a cat kept at a nearby shrine, make the connection and deduce the boy’s reason for lying. Recognizing a lie is just the first step towards the truth; realizing why someone lied is what bridges the communication gap between people. Exposing a lie by itself may just lead to hurt feelings or mistrust, but when you know why a person lied, exposing their lie then provides an opportunity to better understand them, recognizing what that person is trying to do and giving you a better grasp of how to respond to them.

Iwai serves as Kanako’s friend and mentor as she tries to better understand the feelings behind the words people say to each other. He welcomes and recognizes the utility and potential for good Kanoko’s ability to perceive lies and, though his intentions aren’t entirely altruistic, he accepts her for who she is wholeheartedly and honestly in a way no one else ever had. Under his wing as a fellow detective, Kanako witnesses examples of lies told to spare the feelings of the person being lied to, in one case confidently and in the other out of desperation, both cases of someone not wanting a person they care about get hurt or feel let down. The black-and-white antagonistic relationship she has with lies is transformed back into an inquisitive interest in the way people think, wanting to better understand why someone lied to better help the person being lied to.

While the thematic dynamic of Kanako and Iwai’s relationship is compelling, they’re also just really fun, likable characters who bounce off each other endearingly. Kanako’s social anxiety and feelings of isolation are easy to sympathize with and it’s really heartening when she is shown kindness by Iwai and others, and very cathartic and emotional when she tears up realizing he’s not lying to her about accepting her as she is. Kanako wants to do right by others and hates when good people are being lied to or manipulated, instinctually calling out a lie made towards good people due to her sense of righteousness and willing to reveal her powers and risk people perceiving her as weird if it can convince someone she’s telling the truth about some timing important. Kanako’s motivated by a strong desire to help others and the effort she’s willing to make to follow through even when she’s out outside her comfort zone establishes her as an admirable and endearing protagonist.

Iwai, meanwhile, is an aloof goof who can be a little overly motivated by food and money and enjoys teasing his friends for his amusement. The silliness of his character belies the emotional intelligence and observational skills that make him an admirably perceptive and thoughtful detective, and his good heart shines through his kind words and acts to help uplift other people, be them his friends, clients, or even a misguided would-be criminal. Together this pair has a very sweet friendship and mentorship between detective and disciple, and comedically, Kanako can play the straight man to Iwai’s sillier antics or join him in indulging in salivating over food or celebrating a good payday and get excited over eating chestnut rice. These moments where the two are on the same goofball wavelength are adorable, and seeing Kanako grow in the span of this volume from a lonely girl with low self-esteem to a more cheerful optimist whose biggest worry is getting to eat something tasty and whose biggest want is to help her friend’s business grow is really sweet and satisfying.

Ritsu Miyako has drawn this story as thoughtfully as she has written it. Her author’s comments remark on the research she put into depicting kimonos and hairstyles accurately, and indeed, the kimonos she draws have beautifully detailed patterns, from Kanako’s pentagonal flower pattern to the more illustrative and varied flowers featured on Chiyo’s kimono. The difference in the complexity of those examples also speaks smartly to visually communicating the class divide between those characters, which can be reflected in how attire differs between other characters in the series as well. Hairstyles also characterize the differences between characters similarly, with more complex or slick hairdos belonging to more wealthy folk, but even then there’s a difference in how a young girl like Chiyo styles her hair compared to her mother. I also like how Miyako textures hair by having them gradient towards the light source, leaving the topmost part of their hair white as a highlight, which just gives their hair a fully textured and shiny quality. Miyako takes care to portray a variety of different characters with different looks and physiques, and I appreciate the thought and care that went into characterizing them through how they look as much as their personalities.

While the series is not necessarily background-reliant there is also careful attention paid to the look of the architecture and the details in places like the entryway of Iwai’s home, which has all sorts of clutter strewn about on the floor and stairs, or the sparklingly spotless and ornately decorated rooms of the Fujishima’s, communicates a lot about those characters through the environment they live in. While the staging and layouts are straightforward, Miyako often crafts some really standout panels employing a clever use of space and perspective, a particular highlight being a slanted trapezoid panel in the second chapter where a man from a first-person perspective is shown pointing his index finger past Kanako to finger out a woman in the far distance. Dynamic illustrations like this are used sparingly but impactfully, effectively communicating the senses and feelings they need. Everything about the series, from art to writing, feels well-thought-out in construction and intent.

Perhaps the most standout and clever artistic choice is having the speech balloons be filled with a muddy gradient texture when a character is lying, which stands out against the regular pure white speech balloons. Props must also be given to the distinct font used for the lettering of lies, which is a much thicker, stiffer, and angular-looking font compared to the regular speaking font. This font both captures the “metallic” feeling Kanako perceives lies as having, as well as just immediately visually stands out to the reader as something off from the usual in a way that compensates for our inability to hear the aural difference Kanako describes for ourselves. Not all lies told use this muddy balloon and stuff font pairing, as an important lie told later in the first chapter eschews both, but it is a clever visual signifier used impactfully. In general, the font choices are smartly used for different contexts, like a thinner more ballpoint pen-looking font used for asides or a bolder, thicker, blockier font used for flashbacks, and I appreciate making those distinctions for tone and context.

I have a few observations about lettering choices that weren’t detractors but didn’t work as well for me. There are times when I would’ve preferred the series relettered the sound effects entirely rather than annotate them next to the original Japanese in the same panel. It’s a practice that can clutter up the page and distract from the visual impact of particularly large sound effects that best work when you can understand at first glance. There are also times when SFX are inside world balloons that I think should’ve been relettered; while these balloons are often transparent and would require some redrawing and touch-up, dialogue inside similar balloons was redone, and I think it would’ve made sense. But there is also some statement text that is left in Japanese with English lettering to the side that range from short phrases like “a total mess” to longer thoughts like “he’s got a curiosity of steel!” that I also find odd was left intact without being lettered over. None of this is too distracting and hardly impedes my enjoyment of the series, but I do wonder if the series would have benefited in some areas from a lettering replacement and redraw approach rather than the annotation style.

I also want to highlight translator Molly Rabbitt’s deft translation work and writing. The series is predicated upon understanding the nuances of people’s words and understanding the meaning behind them, so a lot of thought must’ve gone into making choices that carefully reflect the intentions of the characters in a consistent way, particularly when it comes to a character who repeatedly lies in the last case in the volume. There’s one sequence especially, where Iwai is testing the conditions and circumstances in which Kanako’s lie-perceiving ability works, where a slight change in how something is phrased makes a critical difference in whether Kanako interprets two very similar statements as a lie or not. When a choice in verbiage is that particular, figuring out how to communicate that nuance must be a delicate challenge, so the fact that the series reads so naturally in English without anything feeling lost in translation is a credit to the talents of the translator and editor in replicating the original intent.

Usotoki Rhetoric was championed as one of the most anticipated new releases to look out for by shojo and mystery manga connoisseurs, and its fans told no lies! I find it interesting we’ve gotten the English release of both this series and another early Showa-set mystery detective series with a female protagonist, My Dear Detective: Mitsuko’s Case Files, around the same time, and what’s great is that they’re both very different approaches to the genre. Whereas My Dear Detective uses its setting and the detective profession to explore who people are by navigating themes of identity and personal expression, Usotoki Rhetoric is about exploring why people are. It’s about the lies we tell and why we tell them, whether we mean what we say and say what we mean. The dynamic between Kanako and Iwai and how their respective skills play off each other is cleverly utilized narratively and thematically. The series’ mysteries are both about figuring out how to expose someone’s lie and figuring out why they told the lie in the first place, shifting the focus of the mysteries from a question of who or how, as would be the focus in other mystery series, to a question of why. This is a series about wanting to understand lies to better understand people, and helping someone through the transformative powers of empathy and kindness, and I couldn’t help but be enamored by the sincerity of its rhetoric.