Story & Art by Aidalro

Translation by Alethea Nibley & Athena Nibley

Lettering by Jesse Moriarty

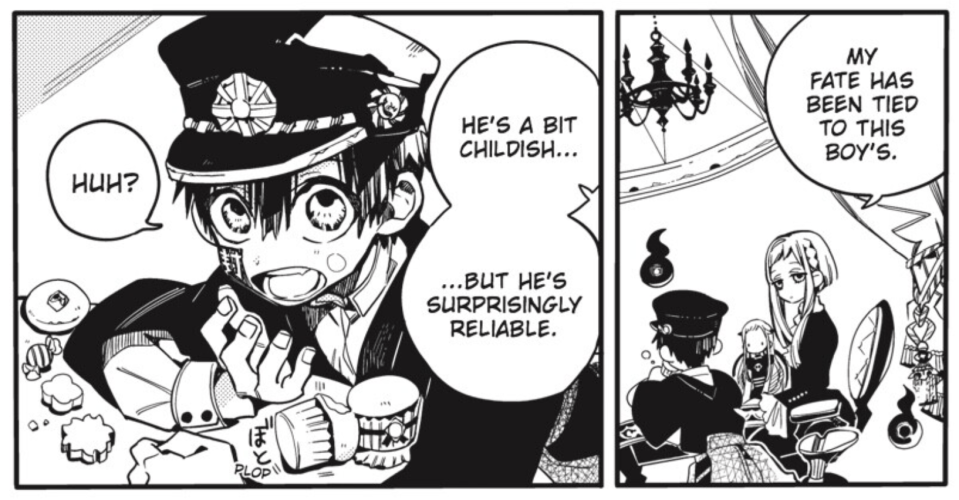

As the progression of time becomes a more prominent motif in Hanako-kun’s narrative, so too does its art emphasize it. The weight and impact of Hanako-kun’s story couldn’t succeed without Aidalro’s precise paneling drawing the reader into its pace, letting you linger in the world to soak up evocative emotions. There are two particular sequences in these volumes where the manga pointedly slows down just to emphasize the emotional weight of a moment in time. The first is when Mitsuba takes a photo of Kou. In a single full-page blocked with three long vertical panels, we see Kou through the lens of Mitsuba’s camera from his first-person perspective. Kou’s naturalistic gestures indicate the quickness and mundanity of this moment, but the three-panel pacing and full-page dedication to it emphasize its significance to Mitsuba.

The pacing of the panels depict Mitsuba first seeing Kou through the lens of his camera, and then lowering it for the final panel to see him with his own eyes. This is why the vertical length of the panels and their layout is so significant. There is a black-filter effect cutting off Kou’s body for these first two panels, reflecting the scope of the camera’s field of vision, and dissipating in the final panel. The effect illustrates how Mitsuba has before only seen the world and other people, like Kou, through the abstracted lens of his camera, narrowing his field of vision and relegating him to a voyeuristic bystander. By lowering the camera, Mitsuba and Kou are now genuinely interacting with each other. Mitsuba only takes pictures of what is important to him, immortalizing impermanent memories. Here, he has decidedly chosen to take a picture of Kou in a natural state, wanting to treasure a memory of his friend as he was. Mitsuba was a character just introduced a chapter prior, but this one sequence conveys so much of his emotional development and character growth in a single page, without him appearing on it.

A similarly subtle but significant moment of time is emphasized when Hanako teams up with Akane at the end of volume 5. This is also a three-panel sequence, but with a horizontal layout a widened gutter between the second and third panels, and the first two panels being rectangular while the third is pentagonal. The action is simple; the first two panels show Hanako walking toward Akane from a shot of their feet, with the third being a low-angle shot of Akane and Hanako looking at each other. Once again, this is a fleeting moment in time being exaggerated through communicating the action between multiple panels. The effect is to emphasize the weight of Hanako still walking toward and confronting Akane despite his insults. By following up the spatial repetitiveness of the first two panels, the third panel’s pentagonal shape has the effect of framing Hanako and Akane, the widened gutter also emphasizing this moment between them.

This is where the choice of having the first two panels focus on their feet plays in. Having two panels dedicated to Hanako stepping forward emphasizes that he is not running away from confronting someone who won’t forgive his past. The third panel revealing their faces shows that Hanako is taking this in stride; his smile betrays no frustration, but genuine amiability in the face of Akane’s stoic disdain. Once again, character growth is communicated through slowing down a moment in time to emphasize it. The ability to manipulate the reader’s sense of time is among comics’ greatest strengths, and Aidalro masterfully plays with their characters’ relationship with time in their art and storytelling.

The emphasis on time in these volumes is a natural evolution of the story’s established focus on change and fate. There are two modes in which these themes are explored: the personal and the external. The personal question facing the characters is whether it is possible to change who they are. Most of the characters wish to be something they’re not currently; Nene wants to be more popular, Akane wants to be a more appealing suitor to Aoi, Mitsuba wants to be noticed and accepted, etc. The series navigates the fine line between change as a force of growth versus as an erasure of personal identity. For example, Nene is tempted to become the mermaid queen for the love and reverence she craves, but doing so would mean discarding her human identity and relationships with her friends, particularly Hanako. Similarly, Mitsuba changed his personality to be more genial upon entering middle school to make more friends, only to find himself being forgotten by his classmates instead. Akane’s efforts to make himself more appealing to Aoi, meanwhile, are so fruitlessly in vain as to rot any satisfaction he could have in his accomplishments. By trying to force themselves to become something they didn’t want to be to try and get what they want, neither of these actually experience personal growth or achieve their goals. Hanako-kun depicts change instead as an effort of self-reflection and acceptance, realizing your limitations and trying to improve on them to be of better help to other people rather than to become more appealing to them. By focusing outside themselves, Nene and Kou are shown to make strides in their own maturity and capability, helping other people through their problems and more confident in tackling their own.

However, the series also brings into question whether someone can actually change who they fundamentally are. Hanako grapples with this question the most, not forgiving himself for his past sins or seeing himself as worthy of redemption. Hanako relapses into more violent behaviors whenever pushed, like when he pins down Nene after Tsukasa’s appearance rattles him. Hanako doesn’t think spirits like himself are capable of change, believing that if you can’t do something in life you’ll be unable to achieve it in the afterlife. The dead have no future, and existing as a spirit is an eternal hell of regret and stagnation, wherein the only escape from one’s misery is destruction.

Hanako’s defeatist philosophy is challenged by other characters with conflicting ideas about personal change. Akane shares the viewpoint that no matter how much someone tries to atone for their past, they cannot erase what they’ve done, especially in the case of murderers. While Nene and Kou believe that Hanako is a good person, the question remains whether his good deeds outweigh the bad and whether the bad in Hanako is really gone or just suppressed. The series posits that while people can change, there’s always the temptation and danger of regression. The person who you once were doesn’t just suddenly go away, but your past self exists simultaneously with your present. It can and will come back to haunt you, literally in the case of Tsukasa for Hanako. In order to truly change, someone must be willing to both accept their past and strive to move forward. There can be no change if there is no desire to live.

While the series is optimistic about personal growth, the characters must also challenge an intangible external force of change: fate. Hanako and the other spirits believe that the world is governed by unassailable rules, and that trying to defy fate is pointless. Tsuchigomori’s books foretell the futures of every student, documenting their entire lives, and he’s never seen anyone change their life’s story aside from Hanako. Hanako and other spirits are resigned to the status quo of predetermination. They accept fate as an immutable force and rather than fight it try to make the most of the time and opportunities they’re given. This is also why Hanako doesn’t believe change is possible after death, because when someone dies time essentially stops for them. A spirit will always remain in the state of how they died physically and mentally because that’s just how their life was meant to go.

As such, a conflict develops between Hanako and Kou in these volumes over defying fate and changing it with their own will. Hanako doesn’t think to challenge Nene’s fate, just wanting to make her as happy as possible in the time she has left. Rather, he doesn’t believe there’s anything he can do, so he won’t even try. Where Kou differs is that he wants to make the effort. Rather than simply accept the status quo as just the way the world works, Kou wants to change the way the world works to help his friends. While Hanako will only operate within the system of fate, Kou seeks to dismantle and rebuild it. It’s not that Hanako doesn’t care about Nene and her life as much as Kou, but he’s already given up on trying, afraid of hurting her and himself if he was honest about the situation and his feelings. Kou recognizes that challenging fate is a daunting task, but he’s willing to use the powers he has and try to make a difference, and it is only through such efforts that change will occur.

While Kou challenges the rules of the world to rebuild it, Tsukasa does so to break them. Tsukasa is introduced as Hanako’s veritable evil counterpart, a dark mirror of him in appearance, objectives, and relationships. While sharing Hanako’s playfulness on the surface, he’s his polar opposite in every other way; callous, manipulative, and murderous. At the crux of their conflict are their differing philosophies about how people should live. Despite Hanako’s fatalism, he sees life as precious and tries to help people live their best lives to the best of his power. Tsukasa, meanwhile, doesn’t care about the lives of others and will destroy them to entertain himself or just for his own curiosity. Essentially, Hanako believes that living involves being considerate of others while Tsukasa believes it is purely a pursuit of self-interest.

Consequently, they also have different perspectives on the metaphysical rules of the world. Hanako strives to maintain the balance between the worlds by encouraging compromise between people so they can live harmoniously. Tsukasa, however, wants to break the world’s rules to create a consequence-free hedonistic environment; a selfish world in which people freely act in their own interests regardless of how much they’ll hurt others in the process. Their different philosophies about life also extend inwardly; unlike Hanako, Tsukasa doesn’t have any regrets over the past. Though he teases and toys with Hanako, it doesn’t even seem like he actually resents his brother for murdering him. Tsukasa believes in forgiving people for their selfishness, not begrudging them for freely pursuing their own interests. Tsukasa’s philosophy adds another interesting wrinkle to Hanako’s guilt and redemption arc; how can he redeem himself when the person he wronged doesn’t even care? Their conflict further emphasizes how Hanako must forgive himself, confronting and accepting Tsukasa and the consequences of his past, if he hopes to stop him and move forward.

At its heart, Hanako-kun is a story that espouses that change is possible for anyone willing to try. It’s about not giving up on the future without fighting for it first. Change starts by being kind to yourself, accepting your past and who you’ve been, learning from your mistakes to mature into the person who you want to be. You can become a better person and improve your life, so long as you make the effort. These themes are relatable life lessons that should resonate with readers regardless of age, with Hanako’s arc exploring how even if you’ve messed up before, it’s never too late to change. Hanako-kun embodies these temporal themes in every facet of its storytelling, and I’m excited to see how they’ll change over time.

comments (0)

You must be logged in to post a comment.